The Missing 300,000 Years: What Life Was Really Like Before Civilization

When you think of human history, your mind likely jumps to the pyramids of Giza, the Roman Colosseum, or the marble statues of Greece. These are the landmarks of “civilization,” the period defined by cities, writing, and states. However, modern humans have existed for over 300,000 years. Everything you learned in school covers less than 2% of our journey.

Where is the other 98%? For 295,000 years, our ancestors lived full, complex lives without a single written record. They were not “primitive” versions of us; they were us—anatomically and cognitively identical, with the same capacity for love, grief, curiosity, and genius.

Anatomically Modern, Mentally Alien?

Around 315,000 years ago, in what is now Morocco, people emerged who looked just like you. If you put them in modern clothes and gave them a smartphone, they could walk down any street today without attracting a second glance. Yet, for a quarter of a million years, they lived in a relationship with the world that is utterly alien to modern minds.

For over 100,000 years, their tools and lifestyles remained stable, almost indistinguishable from our Neanderthal cousins. This creates a fascinating paradox: the hardware (the brain) was ready, but the software (culture and symbolic thought) took time to boot up. The first signs of this “software update” appeared about 100,000 years ago in South Africa, where archaeologists found processed red ochre and shell beads—objects that served no survival purpose other than decoration and ritual.

The Original Affluent Society

We often imagine the Stone Age as a time of constant, grunting struggle. Modern research suggests the opposite. Anthropologists have labeled hunter-gatherer groups as the “original affluent society” because they satisfied their material needs with a fraction of the labor we perform today.

A typical day for your Paleolithic ancestors involved only three to five hours of work—gathering plants or hunting game. The rest of the time was spent socializing, playing with children, making art, and telling stories. Because they moved frequently, they couldn’t accumulate “stuff,” meaning they weren’t tied down by possessions or social hierarchies. They were tall, well-nourished, and generally healthier than the early farmers who would eventually replace them.

The First Masterpieces

The most staggering evidence of prehistoric genius is found in caves like Lascaux and Chauvet. These are not crude doodles. They are masterpieces of perspective, shading, and movement. Some of these paintings are 36,000 years old—meaning they were already ancient history when the Egyptians were building the pyramids.

These artists worked in the deep, dangerous dark, using lamps fueled by animal fat. They used the natural contours of the rock to give their bison and lions three-dimensional volume. They didn’t just paint what they ate; they painted the powerful carnivores they respected and feared. This was the birth of spirituality and the beginning of the human need to transform the world into something sacred.

Engineering in the Ice Age

Survival in the depths of the last Ice Age required more than just fire; it required high-tech engineering. Humans invented tailored clothing—fitted garments with watertight seams sewn with delicate bone needles—to survive Arctic temperatures.

In the treeless steps of Eurasia, where wood was scarce, they built “mammoth bone houses.” These circular dwellings, framed by mammoth tusks and skulls, were sturdy enough to withstand the crushing winds of the tundra. They managed a complex fuel economy, burning bone to stay warm and developing long-distance trade networks to swap high-quality flint and obsidian for tools.

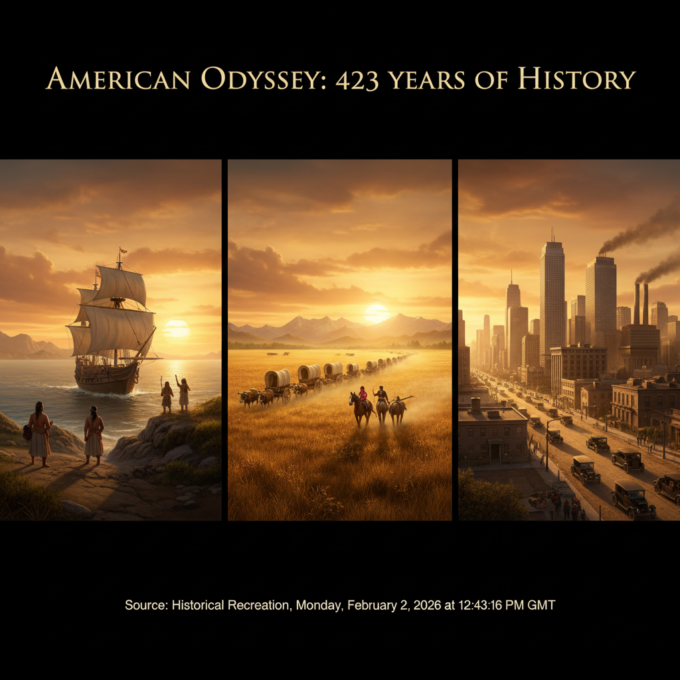

The Great Migration

Perhaps the greatest feat of this era was the global expansion. Carrying nothing but stone tools and the knowledge in their heads, humans left Africa and reached every corner of the globe.

They reached Australia at least 50,000 years ago, a journey that required crossing nearly 60 miles of open ocean. This wasn’t an accident; it was a deliberate voyage of exploration by people who understood the stars and the currents. Within 50,000 years, human fires were burning on every continent, from the rainforests of the Amazon to the frozen plains of Siberia.

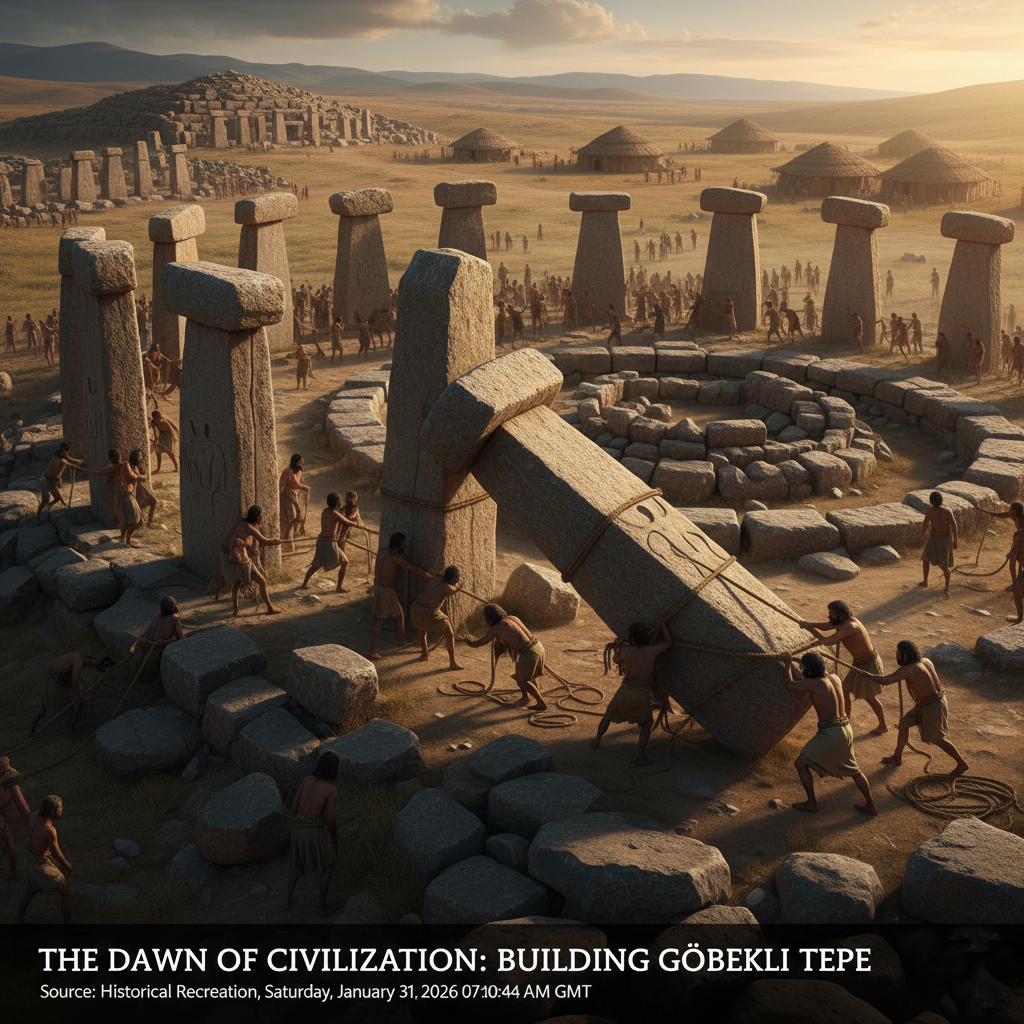

The Turning Point: Why We Left Paradise

Everything changed roughly 12,000 years ago. As the Ice Age ended, humans began to experiment with the soil. Agriculture wasn’t a sudden invention; it was a slow, uneven drift. Farming supported more children, but at a high cost: farmers worked harder, ate a less varied diet, and suffered from new infectious diseases that thrived in permanent settlements.

With the surplus of the fields came the birth of hierarchy. Once grain could be stored, it could be controlled. The egalitarian bands of the Paleolithic gave way to the kings, priests, and bureaucracies of the first cities like Jericho and Uruk.

The Hunter-Gatherer Within

We live in a world of concrete and glass, but we carry a Stone Age brain. Your need for social connection, your love for a flickering fire, and even your late-night anxiety are relics of a time when isolation meant danger and the stars were your only map.

Understanding our missing 300,000 years isn’t just about curiosity. It’s about remembering that we are veterans of survival, sculpted by a history much older and more epic than anything found in a textbook. We were always artists, always explorers, and always human—long before the first word was ever written.

Leave a comment