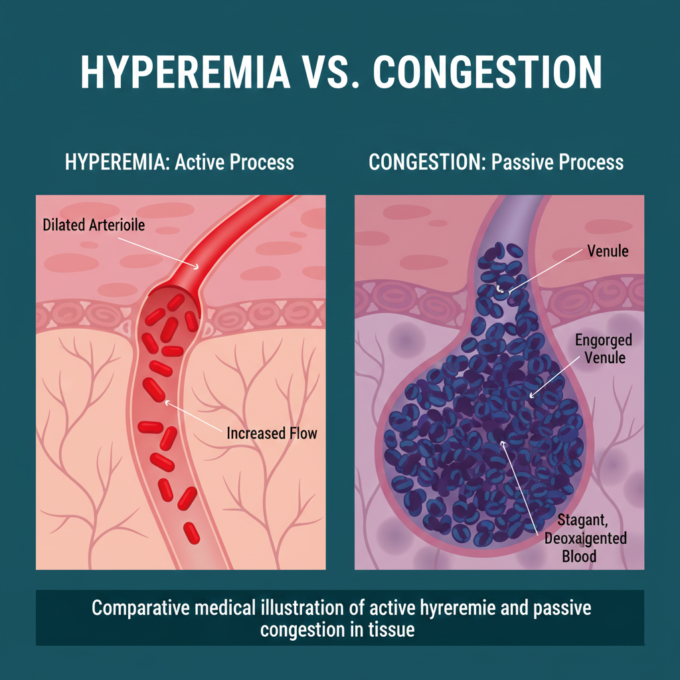

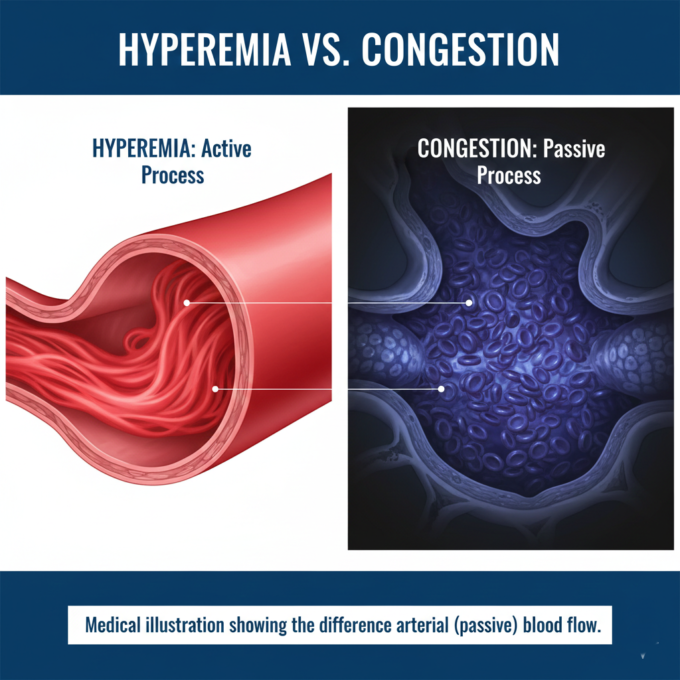

Hyperemia vs. Congestion: The Basic Difference

Before diving into specific organs, it is vital to distinguish between these two states of increased blood volume:

- Hyperemia: An active process. It occurs when arteries dilate, sending more oxygenated (pure) blood to an organ. This makes the tissue appear bright red (erythema). Examples include blushing or the redness seen during inflammation and exercise.

- Congestion: A passive process. It occurs when the venous drainage of an organ is impaired or obstructed. This causes deoxygenated (impure) blood to pool, making the organ appear blue or dusky (cyanosis).

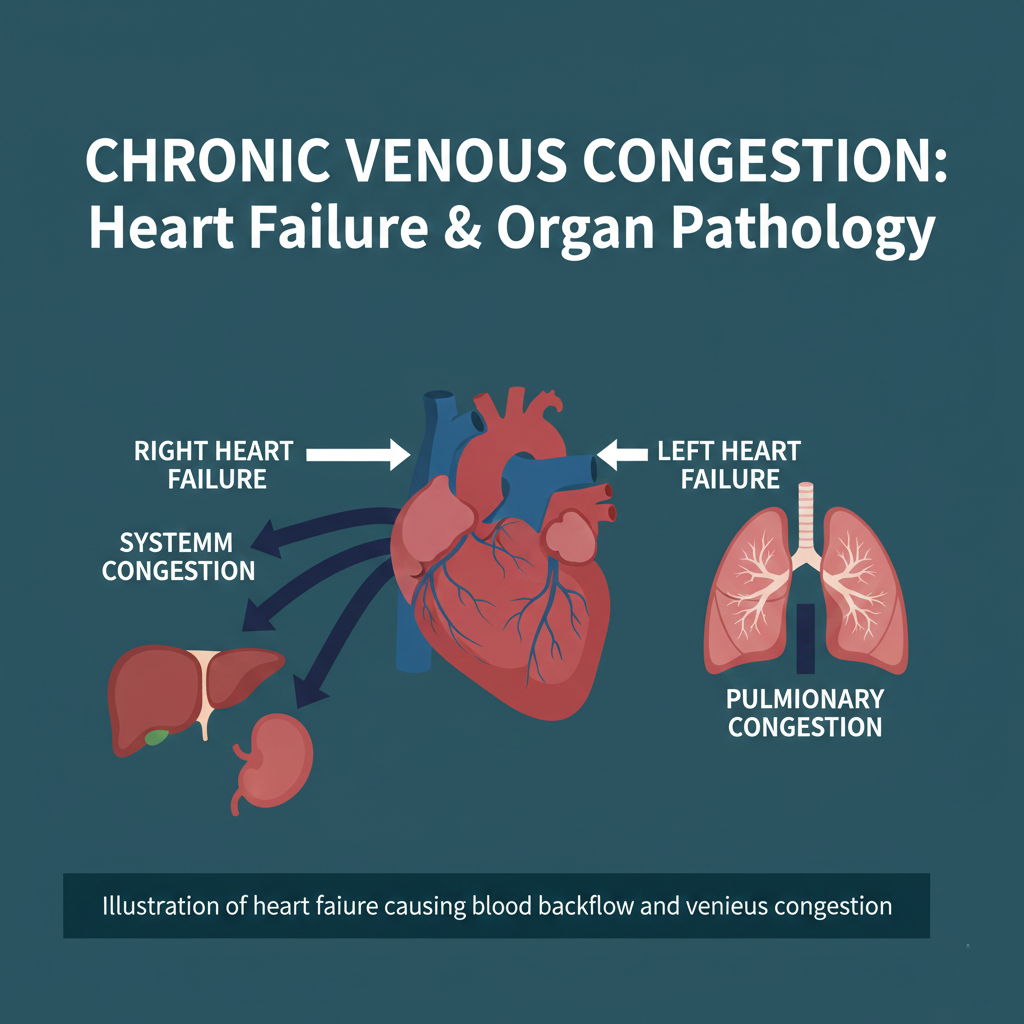

The Heart Failure Connection

Chronic Venous Congestion is usually a secondary effect of heart failure. The “backflow” of blood determines which organs are affected:

- Left Heart Failure: When the left ventricle fails to pump blood forward into the aorta, blood backs up into the left atrium and then into the pulmonary veins and capillaries. This leads to CVC of the Lung.

- Right Heart Failure: When the right side of the heart fails, blood backs up into the superior and inferior vena cava, affecting almost every other organ in the body, most notably leading to CVC of the Liver and Spleen.

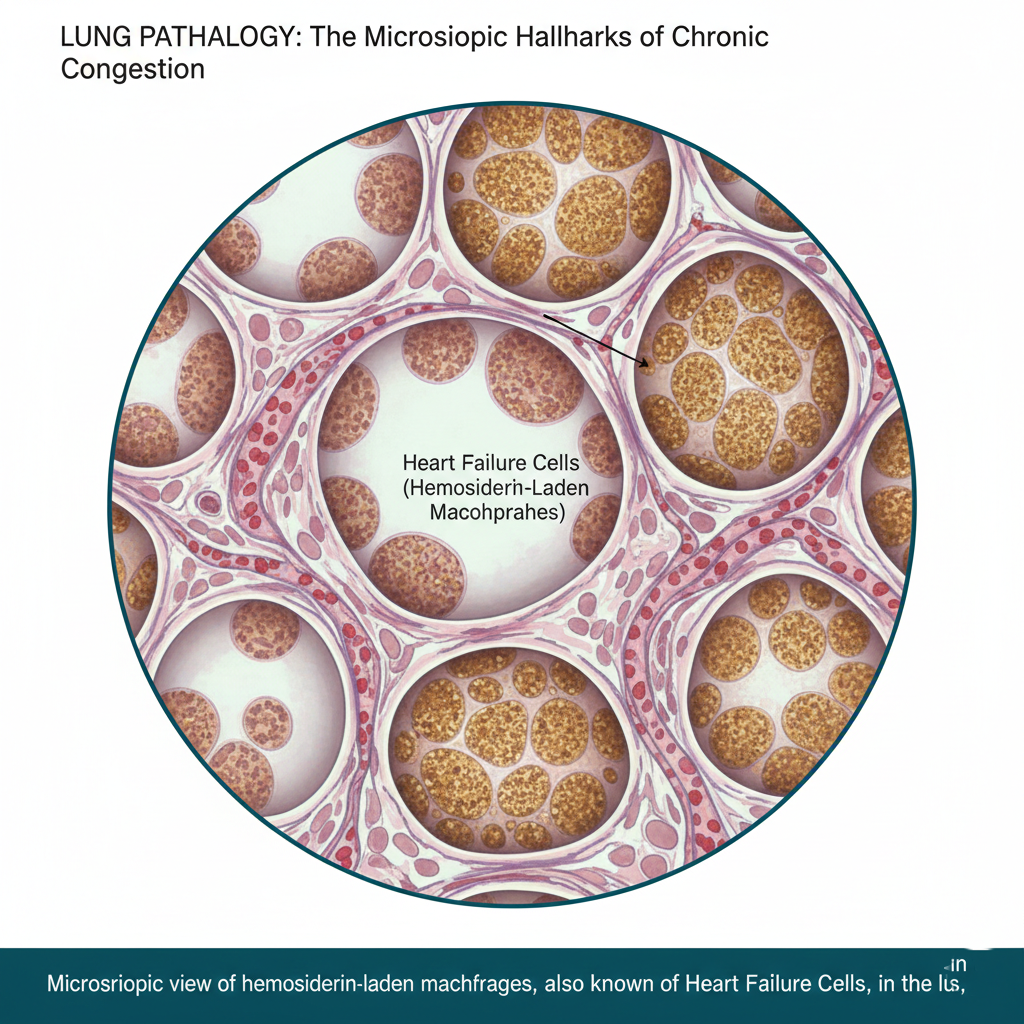

CVC of the Lung: Brown Induration

In the lungs, chronic congestion leads to a condition often described as “Brown Induration.” Because the lungs are overfilled with blood, they become heavy and firm.

Microscopic Findings:

- Dilated Capillaries: The small blood vessels in the lung walls become engorged.

- Edema: Fluid leaks from the high-pressure capillaries, first into the surrounding tissue (interstitial edema) and eventually into the air sacs (alveolar edema), which causes breathing difficulties.

- Heart Failure Cells: This is a hallmark sign. When capillaries rupture, red blood cells escape into the air sacs. Macrophages (immune cells) then eat the broken-down hemoglobin, turning into hemosiderin-laden macrophages. Despite their name, these cells are found in the lung tissue, not the heart.

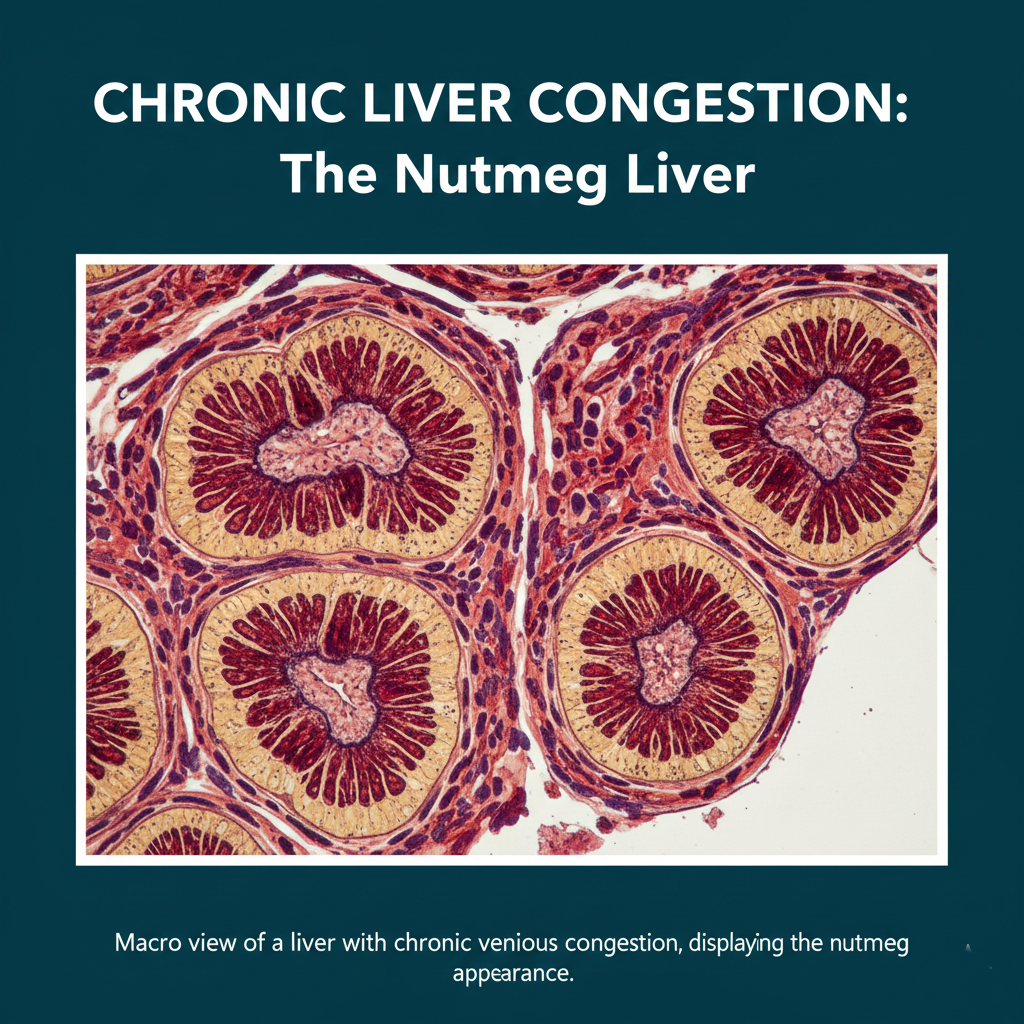

CVC of the Liver: The “Nutmeg” Appearance

The liver has a complex hexagonal structure (lobules) with a central vein in the middle and “portal triads” at the corners. Because of this unique layout, congestion creates a very specific visual pattern.

Why is it called “Nutmeg Liver”? When the liver is congested due to right heart failure, the backflow of blood hits the central veins first.

- The Red Areas: The tissue around the central vein undergoes hemorrhagic necrosis. The pooling of deoxygenated blood and the death of liver cells make these areas look dark red.

- The Yellow Areas: The liver cells further away (near the portal triads) don’t die immediately but instead undergo “fatty change,” which makes them look yellow or tan.

The alternating pattern of dark red (dead/congested cells) and yellow (fatty cells) mimics the inside of a nutmeg seed.

Chronic Venous Congestion is more than just “too much blood.” It is a visual and microscopic map of how a failing heart affects the body’s vital organs. By recognizing signs like heart failure cells in the lungs or the nutmeg appearance of the liver, medical professionals can trace these symptoms back to their systemic roots.

Leave a comment