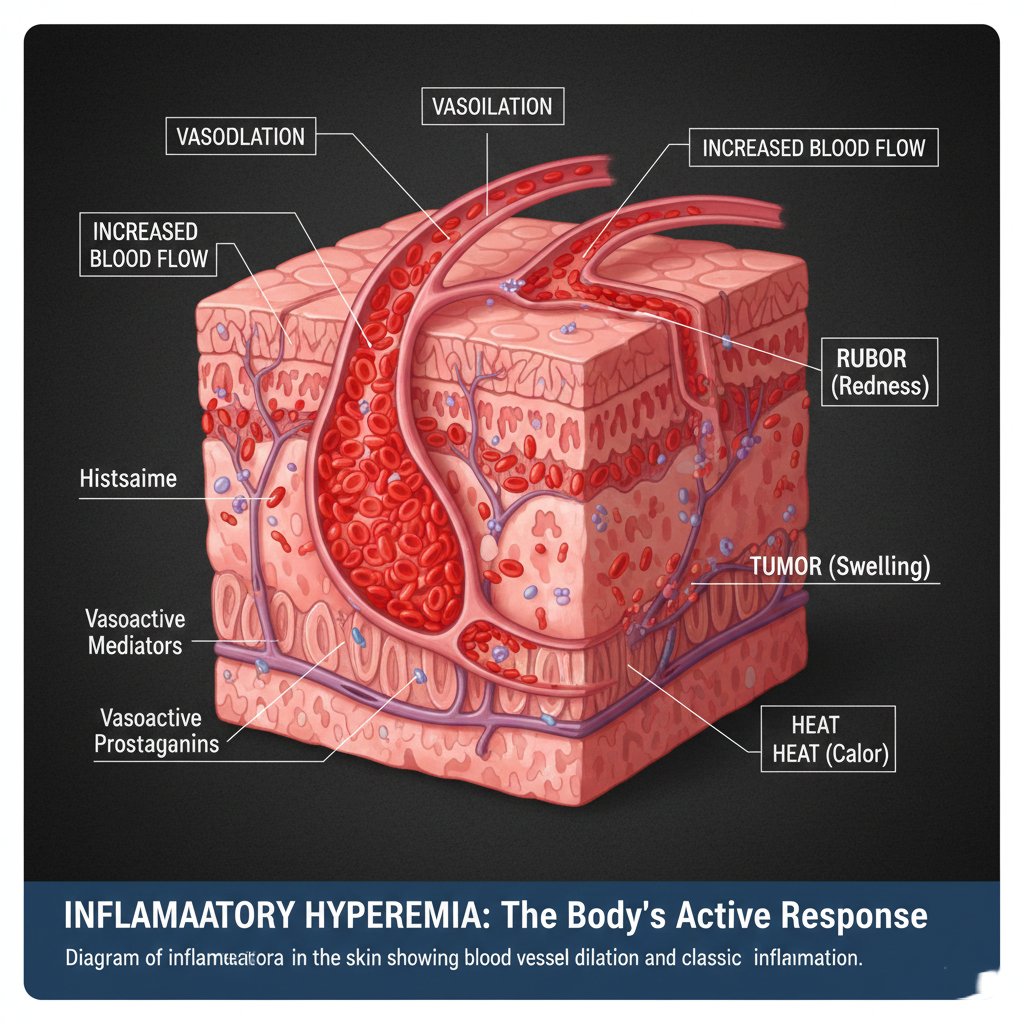

Hyperemia: The Active Response

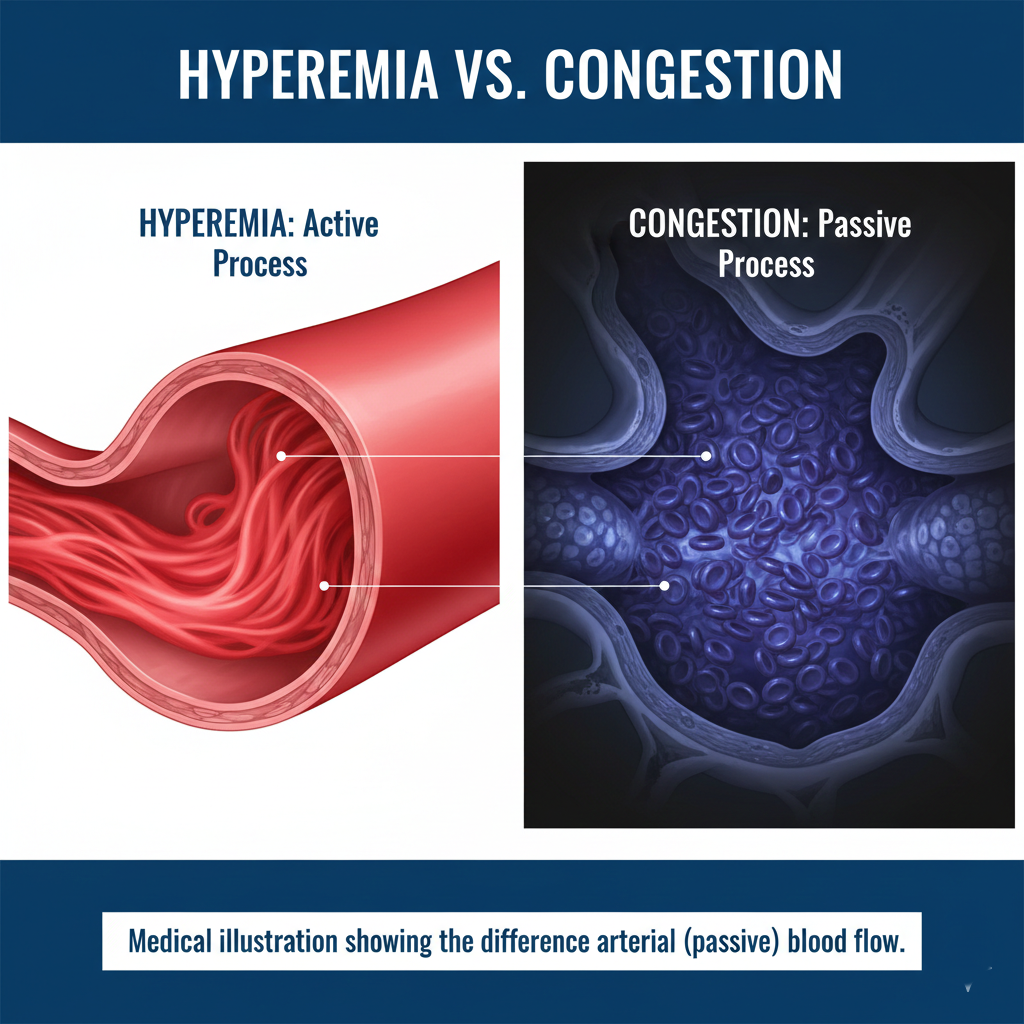

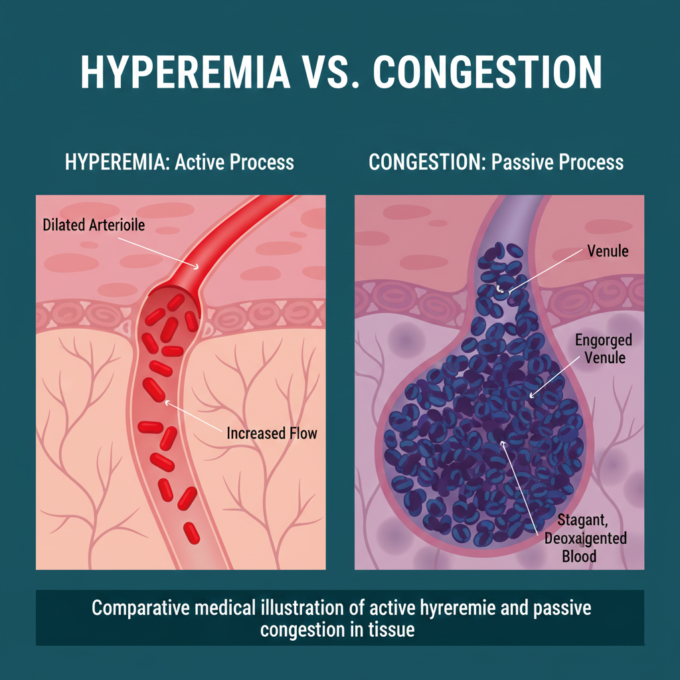

Hyperemia is an active process resulting from augmented blood flow due to arteriolar dilation. This increased volume of blood is usually a physiological response to meet higher functional demands.

- Active Hyperemia: This occurs on the arterial side of circulation. Common examples include:

- Physiological: Skeletal muscle during exercise or the “menopausal flush.”

- Inflammatory: The most striking form, where vasoactive materials cause blood vessel dilation, leading to the classic signs of redness (rubor), swelling (tumor), and heat (calor).

- Reactive Hyperemia: This happens after a temporary interruption of blood supply (ischemia). Once blood flow is restored, the tissues appear redder than normal because they are engorged with oxygenated blood.

Congestion: The Passive Accumulation

Unlike hyperemia, congestion—also known as passive hyperemia—is a passive process resulting from impaired outflow from a tissue.

- Symptoms and Color: Congested tissues have an abnormal blue-red color known as cyanosis. This is caused by the accumulation of deoxygenated hemoglobin in the affected area.

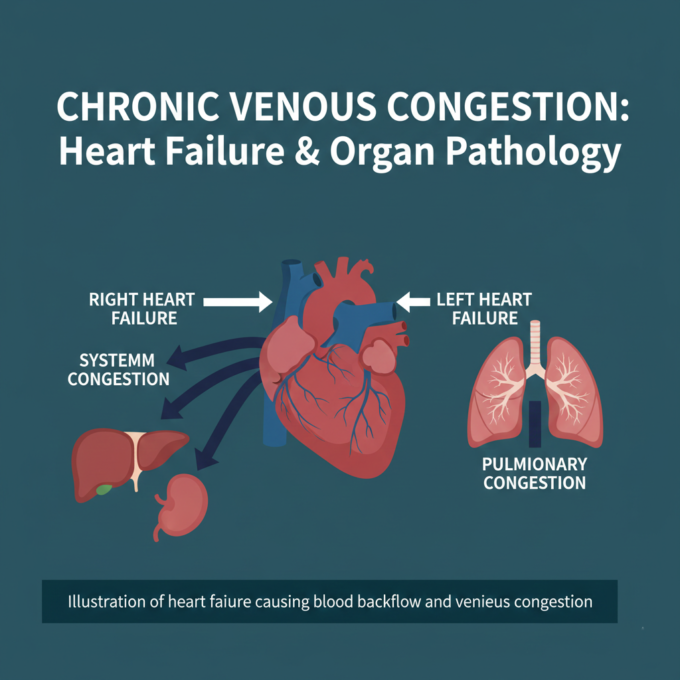

- Systemic vs. Local:

- Systemic Congestion: Often caused by cardiac failure (left or right ventricular failure).

- Local Congestion: Resulting from isolated venous obstruction, such as deep venous thrombosis (DVT) in a limb.

The Chronic Impact: Lungs, Liver, and Spleen

Longstanding chronic congestion can lead to significant tissue damage, including cell death and secondary fibrosis.

1. The Lungs (Chronic Passive Congestion)

Commonly caused by left-sided heart failure.

- Gross Appearance: The lungs become heavy, firm, and rusty brown. This condition is often called “Brown Induration of the Lung.”

- Microscopy: Alveolar walls thicken with fibrous tissue. A hallmark sign is the presence of “heart failure cells”—macrophages laden with hemosiderin, a golden-brown pigment formed from broken-down red blood cells.

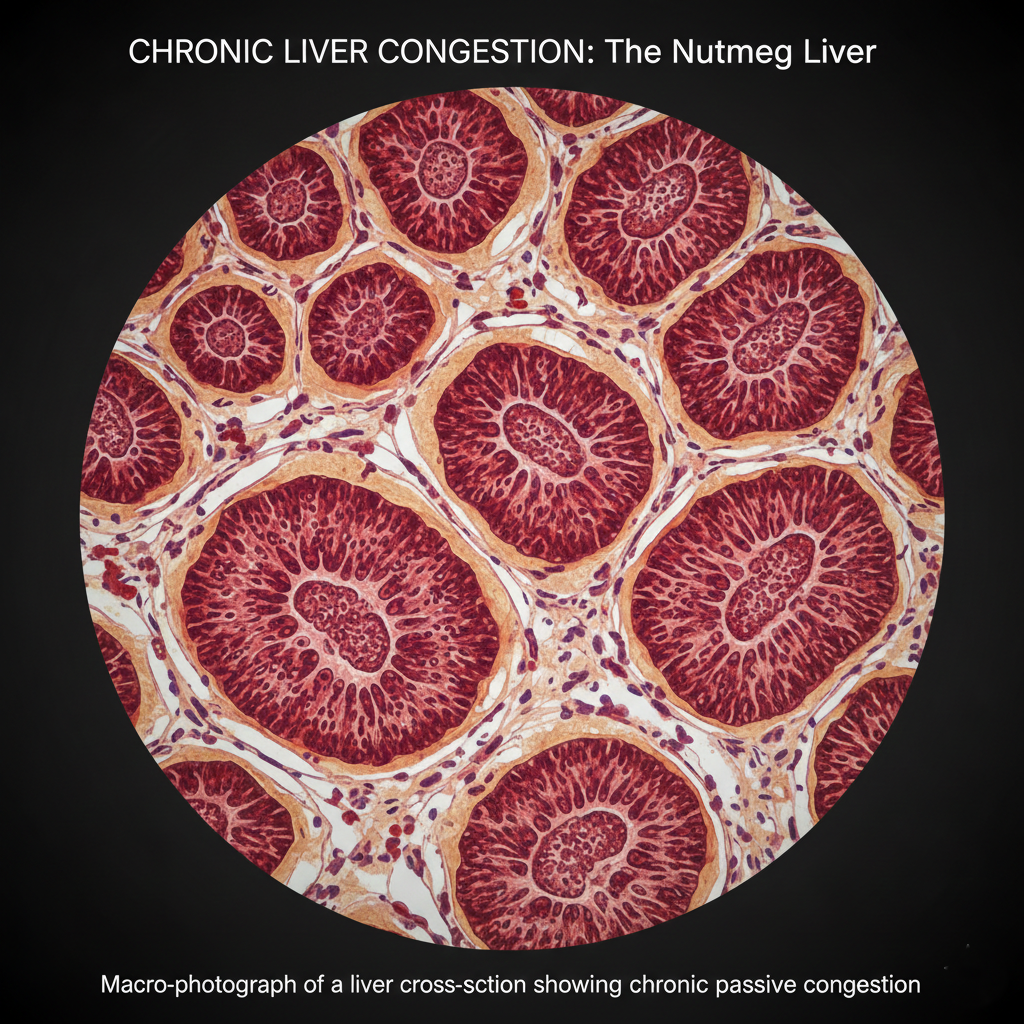

2. The Liver (Nutmeg Liver)

Primarily caused by right-sided heart failure or hepatic vein obstruction.

- Gross Appearance: The liver displays a speckled “nutmeg” appearance, where dark red congested centers are surrounded by paler, unaffected peripheral areas.

- Pathology: Increased pressure causes central veins and sinusoids to dilate, leading to pressure atrophy of hepatocytes and, eventually, hemorrhagic necrosis.

3. The Spleen

Congestion in the spleen is often a result of portal hypertension or cardiac failure.

- Gamma-Gandi Bodies: In chronic cases, small yellow-brown fosi of old hemorrhage, known as Gamma-Gandi bodies, can develop. These consist of fibrous tissue, hemosiderin, and calcium deposits.

- Hypersplenism: The enlarged spleen (splenomegaly) may become overactive, leading to hematologic abnormalities like thrombocytopenia.

Understanding the distinction between hyperemia and congestion is fundamental in medical pathology. While hyperemia is often a temporary and active response to stimuli, congestion frequently signals an underlying systemic issue, such as heart failure, that requires careful clinical management to prevent irreversible tissue damage and fibrosis.

Leave a comment